I hate soybeans,” said Mike, general manager of a country elevator operation in the Corn Belt — throwing the newest monthly P&L off to the side of his desk in disgust.

The noise attracts the attention of Jeff, the elevator’s grain merchandiser, who was passing by. “Well, I guess I don’t hate soybeans, Jeff,” Mike added. “I just hate that we can’t seem to make money handling them. This is the third year in a row with red ink. And we’re already halfway through the crop year.”

Mike leans forward and picks up the printout again, then looking over his glasses, asks Jeff: “So what’s up — you were sure we’d turn this soybean P&L around in February, but the losses are growing.”

Jeff reminds Mike that the extreme winter weather has slowed their shipping, and soaring freight costs have weakened interior basis values. Basis at local crushers dropped 15¢ in February, and export values are off almost as much.

“We’ve shipped as much as we could since harvest but we can’t get ahead. We bought a lot more beans in February at the cheaper values, but basis has slid further. What else could I do?” Jeff replied. “If we liquidate the ownership now, we’re guaranteed to take a big loss and we’re still behind on shipments. But with the weather improving and farm selling slowing, basis should pick up again. Soybean stocks are tight this year, and last summer basis went to more than 200 over November!”

Mike and Jeff’s woes are not unique. Merchandising soybeans has been a tough challenge everywhere for the last three years. Futures have seldom showed more than a token carry — and often had steep inverses. Yet elevators can’t ship as much at harvest (or soon after) as they buy. Short delays can stretch into weeks or months, and buying more soybeans only adds to the problems. Merchandising soybeans has been hardest on Western train loaders this season with freight costs soaring to record levels, nearly $4,000/car on Burlington Northern shuttles at times. Size wasn’t an advantage this year!

Explanations don’t matter

Reality can be difficult to accept, but a merchandising plan has to reflect current circumstances, and traders should also consider potential

“Black Swans.” Before harvest was the time for Jeff to think about what to do if cars weren’t available, or if freight costs were to soar. By mid-summer last year the Nov13/ Jan14 soybean futures spread was rarely as wide as a 6¢ carry, and was inverted by late September. Further, by September 2013, the Jan14/March14 futures spread was inverted by 15-30¢. Planning to carry hedged soybeans beyond Nov/ Dec had “Loss” written on it before the combines rolled. The only salvation would have been if harvest basis collapsed to cheap enough levels to build some carry in futures and allow Dec/Jan basis appreciation to provide some net return.

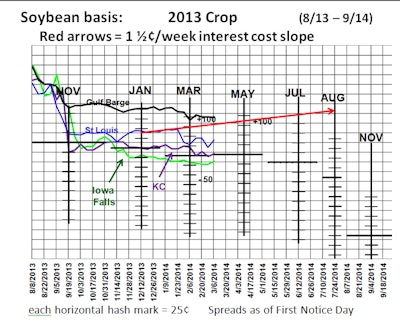

But basis didn’t collapse at harvest; corn and soybean inventories were drained by September, farm bins were mostly empty, and buyers stayed aggressive to avoid missing bushels. The first chart on pg. 42 shows 2013 crop soybean basis at four markets; basis peaked (adjusted for spreads and net of interest holding cost) during Oct/Nov at all of them. The massive export program for China was already in place before harvest began, which supported port values all fall, forcing crush plants to compete in many areas.

The country elevator’s game plan in harvest 2013 needed to reflect the reality of buying against a strong basis with no carry in futures. Protecting profit margins wouldn’t be easy but there were steps to take.

First, consider the “big picture”:

- The U.S. was forecast to have another extremely low ending stocks/use ratio (4.5% in four of the past six years).

- Soybean export sales were huge, and heavily weighted to China for fall/winter.

- Livestock margins were strong which would encourage consumption of meal despite lower animal numbers.

- Soybean futures spreads were inverted, reflecting strong demand and tight supplies.

Second, think and act local:

- Determine the elevator’s realistic shipping capacity for Oct/ Nov/Dec. Allow for slippage; railroads can run late any year, weather can cause delays, etc.

- Set a cap on how much volume to buy, consistent with shipping capacity. (Don’t buy 2 million [M] bushels against a market value if you can only ship 1M.)

- Adjust basis bids downward on purchases beyond your short-term shipping capacity to reflect the cost of having to sell the ownership into cheaper forward values.

- Lock in freight to fix shipping costs against sales. Western shuttle trains could have been booked for Nov/Dec 2013 as late as September for zero to $200/car. By early November those trains cost $1,500 to $2,500/car. Even if freight costs had fallen during harvest, the objective is to eliminate another risk that can erode profits.

- Soaring rail freight forced train-loaders to weaken their buying basis somewhat last fall, but few elevator bids reflected the full cost of securing cars. Setting basis bids much below competitors during harvest is never popular with managers and merchandisers, but buying bushels in inverted basis markets can be a recipe for red ink. The choice is clear: Protect your margin or lose money and be popular.

Selling soybeans for nearby slots in inverted markets isn’t enough, either. You have to be able to execute your sales in the contracted period. Selling for November but having to ship in February because cars didn’t come in would rack up around 18¢ in extra interest costs, for example.

The winter of 2013 could be chalked up as a Black Swan that no one could have foreseen and that disrupted merchandising plans. This winter was extreme, but soybean basis in 2012 crop was eerily similar to this year even though weather was mild and rail freight costs were less volatile. The pattern is shown on the three basis charts on pg. 42: Soybean basis ownership after Nov/ Dec has offered little to no return the past three years. That statement has some qualifications:

- The charts reflect rolling short hedges to each successive futures month in rotation; no pre-setting of futures carries.

- This shows only the spot basis bid from each Thursday using best known published bids.

- In some situations, a seller might have realized a higher value for a given time slot by selling forward.

- The charts also don’t reflect any additional basis “push” a seller may get by negotiating.

- 2013 chart only: Spreads beyond March 2014 are as of mid-March 2014.

- The red arrows represent a 5% cost slope, approximately 6¢/ month, starting around mid- December to show gains/losses for holding past that time slot.

There weren’t many chances to buy cheaper basis during the winter and hold for more than very short periods and gain anything. Looking back over six years, holding would have paid off at times in ’09 and ’10 crops (not shown); the key with those years was that futures were in a carry much of the crop year.

Soybean stocks will be very tight again in the summer of 2014, but holding hedged soybeans until then is unlikely to be profitable. Inverses and interest costs are just too steep: May/Aug futures are inverted by 50+¢, with May/Nov inverted $2.10+.

Being short soybean basis in inverted futures markets with high front-end basis values is a better strategy. But that assumes you have delayed price inventory you can ship first and buy in later.

Looking ahead, 2014 crop futures spreads already offer little carry and Oct-Dec ’14 basis values are very high at the Gulf and PNW. The signs point to another year where holding hedged soybeans past December looks risky. Soybean stocks will be largely depleted by early September and quick-ship basis premiums could roll forward well into harvest.

Watch the pace of new-crop export sales, futures spreads and your pace of purchases. Until or unless basis and spreads show a profitable net carry past December in your cash markets, assume your merchandising plan has to be to sell and ship basis ownership by Christmas. And remember: Planning is only effective when you can execute the plan.

Editor’s Note: Hypothetical performance results have certain inherent limitations, and do not represent actual trading. Past results are not indicative of futures outcomes. Trading futures involves risk of loss.