The U.S. grain industry has anticipated the completion of the Panama Canal expansion since the project was announced nearly a decade ago. It is a vital trade route for agricultural commodities shipped from the East Coast and the Mississippi River destined for Asia and western South American countries.

When fully completed, U.S. exporters and foreign buyers can look forward to reduced transportation and landed costs thanks to the Canal’s new lane of traffic and a new set of locks — doubling the waterway’s capacity. The congestion alleviated will decrease transit times by two to three days for grain and other agricultural goods shipped from the United States to Asia and vice versa.

Although the United States must update much of its inland waterways system to accommodate larger vessels and reap the full benefit of this upgrade, the faster route holds potential for increasing the efficiency of U.S. grain shipments.

All components of the Panama Canal expansion were originally scheduled to be finished by October 2014; however, construction complications and labor disputes pushed the projected opening back to April 2016. At press time, reports indicated that final testing on the expansion would begin in late April and it should be open for commercial traffic in May.

The last 100 years

The French government began to build the Panama Canal in 1881 to connect the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean across the Isthmus of Panama. The canal was designed to provide travelers an alternative to navigating the dangerous Cape Horn route around the southernmost tip of South America. But when the French encountered insufficient funding, a labor force sickened by malaria and yellow fever, and key design flaws, they could not complete

their enormous endeavor.

In 1904, the United States government purchased the Canal Zone for a total of $50 million and spent $375 million to complete its construction by 1914. The 51-mile-long canal connected vessels from one ocean to the other by raising and lowering them nearly 86 feet through a series of three locks.

The United States operated the canal for 85 years until nearly the turn of the century. When it turned over operations to the Panama Canal Authority (ACP) in 1999, the average time vessels spent in-transit through the canal was nine hours, but it rose to anywhere from 13 to 35 hours by 2008, according to the ACP.

In 2007, the ACP announced that an expansion plan of epic proportion, costing $5.25 billion, would be completed by 2014. The main advantage of the expansion for U.S. agriculture is its third set of locks, which will ease congestion at the canal by accommodating vessels with capacities of up to 13,000 to 14,000 shipping containers, called twenty-foot-equivalent units (TEUs). Pre-expansion, the canal allowed for the passage of Panamax vessels that carried only up to 5,000 TEUs. The new post-Panamax vessels will be able to carry up to 85,000 metric tons of grains compared to the usual 55,000-metric-ton grain shipments, according to the USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service.

Expansion plan

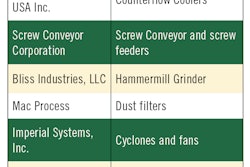

The new locks will be 1,500 feet long, 180.5 feet wide, with a depth of 60 feet. Additionally, the expansion plan consists of three other critical components: the Pacific access channel, navigation channel improvements and improvements to water supply (See table above).

Panama Canal’s role in U.S. grain

According to the Agricultural Marketing Service, the United States is the No. 1 user of the Panama Canal, amounting to two-thirds of the its traffic, and grain tops the list of U.S. commodities shipped through the canal.

The ACP’s report on “Principal Commodities Shipped Through the Panama Canal” shows that in 2014, more than 158 million metric tons of cargo originated from or was destined for the United States.

The figures report soybeans have taken the lead as the top U.S. commodity shipped through the canal, clocking in 19,743.8 million metric tons in 2015. According to the Soy Transportation Council, approximately 600 million bushels of U.S. soybeans annually transit the Panama Canal. Other leading U.S. commodities include corn, sorghum, wheat, rice and barley — shipping a total of nearly 27,532.8 million metric tons altogether through the canal last year.

During the first half of 2015, a record 33.3 million metric tons of grain transited the waterway — representing an 8.5% increase compared to the same period in 2014. A majority of this increased grain trade originated from the United States.

Funding needed to seize the opportunity

The Panama Canal plays a huge role in the trade of U.S. grain, but its expansion highlights some of the challenges facing the Mississippi River’s locks and dams.

According to a Soybean Checkoff-funded study “Panama canal Expansion: Impact on U.S. Agriculture,” the draw area to the nation’s major navigable waterways could expand from 70 miles to 161 miles once the Canal is complete.

With an increased area of the country able to take advantage of the inland waterway system, the demand for barge loading facilities along the country’s major rivers will likely increase.

However, the Post-Panamax vessels require deeper, wider shipping channels, greater overhead clearance, and larger cranes and shore infrastructure. Many of the Mississippi River’s locks don’t meet such requirements because they were built more than 50 years ago — well before the era of supersized 14,000-container vessels. Federal funding is crucial to update the system.

Waterways funding saw a victory in 2015 with appropriators allocating far above the administration’s deficient requested budget. To maintain this momentum, the Ag Transportation Working Group recently appealed to the House and Senate to continue funding on the U.S. inland waterways system. A letter signed by the group’s 20 members asked lawmakers to appropriate the full amount supportable by the diesel fuel tax going into the Inland Waterways

Trust Fund, which should be around $390 million in FY2017.

Additionally, the National Grain and Feed Association requested that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the agency responsible for carrying out Mississippi River improvements, receive the minimum funding level of $3.137 billion for its operations and maintenance account.

The expansion of the Panama Canal holds vast potential to increase the efficiency of U.S. grain exports to Asia and the western South American region, but reaching maximum potential depends on further funding of the United States’ aging inland waterways. The canal’s new, larger lock is projected to open in May, representing an exciting time in U.S. agriculture when its various sectors can come together in support of a common goal. If the United States fails to make investments in our ports, inland waterways and other vital infrastructure, the Panama Canal expansion may truly be a missed opportunity.

Subscribe to Magazine