The Great Plains suffered a terrible year in 1935. Already struggling in the fifth year of the drought, the Plains folk still had to endure one of their single worst days: April 14, 1935. Palm Sunday. Black Sunday. After millions of acres of wheat had already been lost that spring to drought and wind, this day brought another terrifying black blizzard that dwarfed the dust storms that had plagued the Plains since 1932. Starting in North Dakota, this 200- mile-wide monstrosity raced southward at nearly 60 mph and by late afternoon reached Oklahoma with clouds of black dust soaring thousands of feet in the air. Estimates say more than 300,000 tons of topsoil blew away on that one day before the storm exhausted itself. This was the day when reporters coined the term “Dust Bowl.”

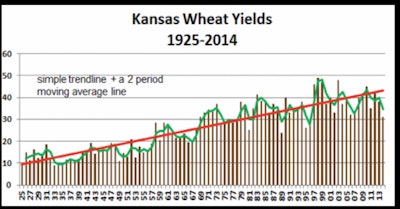

Kansas farmers continued to plant wheat during the Dust Bowl, but yields back then fell by half, to barely 9 bushels/harvested acre three years running (4.8 bushels/planted acre in 1935). The rains didn’t begin to return until 1938-39, and it took until 1942 before Kansas wheat yields recovered to pre- Dust Bowl levels. As the times worsened, acreage declined and some didn’t return to production for years. Kansas, Oklahoma and Nebraska last fall planted a total of 16.1 million (M) acres of wheat, compared to the typical 22M in the 1930s, for example, with a lot of acres shifting over the years into more drought-tolerant sorghum, pasture/hay, and then over to CRP or soybeans.

Author Timothy Egan aptly described that entire era as The Worst Hard Time in his 2006 book of the same name. Unfortunately there’s little written about the impact of those terrible years on grain elevators, but the losses had to be huge. The Kansas wheat crop in 1931 was 252M bushels; in 1935 it was 64M, with Nebraska’s wheat falling from 75M to 17M in 1934, and Oklahoma lost almost 40% of its wheat production.

Cropping and soil conservation practices have prevented the extreme black blizzards seen in the ’30s, but drought has again dug its iron claws into the Plains. USDA forecasts the Kansas wheat crop to fall again to 260M bushels this year, at just 31 bushels/planted acre, the lowest yield since 1995/96. (Trend-line starting from the pre-Dust Bowl days would be around 42 bushels/planted acre.) Oklahoma is even worse, forecast at 19 bushels/planted acre this year for a crop of just 63M — already smaller than in 1931 — with conditions worsening since the May report

Nebraska wheat is now forecast at 55M bushels, which is actually higher than last year though, on a relatively good yield of 39 bushels/ planted acre. The drought’s impact is now squarely on the Southern Plains; the Northern Plains have seen more than enough rain this spring — almost too much.

Corn acreage in the Southern Plains was also hit hard by the Dust Bowl, dropping 60% in the ’30s in Kansas and never recovering to its old highs, and finally rising in Nebraska to 9+M acres again only in recent years.

But what about the commercial sector since those lean years? The elevator industry contracted and consolidated dramatically since the late 1980s after the government liquidated the billions of bushels owned and stored by Commodity Credit Corporation. The commercial sector over time became leaner, and the price run-ups of 2008 forced firms to improve their balance sheets to secure financing to be able to withstand price spikes. But that doesn’t guarantee firms can weather all tough times. The Northern Plains have seen an explosion of upgrading and expansion; there are now over 160 shuttle train loaders on the BNSF — nearly all west of the Mississippi River. That’s a lot of investment to recoup at a time when the China market is in question for U.S. corn exports. And let’s hope the Plains aren’t destined to repeat the 1930s with a catastrophic loss of production.

Across the broader region from Montana south to Kansas, much has been said and written about this year’s rail logistics problems. Stories abound portraying bins as still overflowing with unshipped grain even as wheat harvest nears. The March 1 Quarterly Stocks were higher in the Northern Plains this year, but not shockingly so. March 1 stocks totals of all major grains for KS/MN/MT/ND/NE/ SD, rounded off:

| 3/1/2011 | 3.6B bushels |

| 3/1/2012 | 3.0B bushels |

| 3/1/2013 | 3.0B bushels |

| 3/1/2014 | 3.4B bushels |

Last year those six states then also handled 6.8 billion (B) bushels of 2013 crop production. This summer/fall, potential production for 2014 for this same region could be around 6.6B bushels of wheat, corn, milo and soybeans, excluding minor crops. More storage space has been built in that region which further eases the situation. USDA’s statistics from January 2014 compared to 2013 showed North Plains’ storage capacity rose 100M+ bushels (on-farm plus commercial) from around 8.13B to almost 8.3B bushels — more than enough to handle the 2014 fall harvest. The actual storage capacity is almost certainly larger than USDA has indicated — there’s been no shortage of bin construction in the past year. Storage capacity isn’t distributed evenly, however, and having enough room “on paper” or even in reality doesn’t preclude ground piles, and being a high-speed shuttle-loader hasn’t guaranteed car placement this year.

March 1 stocks decline steadily through spring and summer via exports, ethanol production, soybean crushing, feeding and other commercial uses, which frees up space. And total usage for 2013 crop is almost 3B bushels higher for c/b/w over 2012 crop, so bigger daily disappearance for the summer of 2014 should easily whittle down much of the “extra” 400M bushels seen in the March 1, 2014 stocks in the Northern Plains. A lot of the grain can move locally via trucks and avoid the logjams that have plagued the Northern railroads.

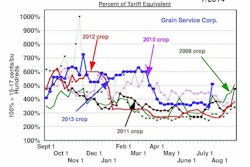

But the grain industry has incurred real costs this year from the railroad delays: millions of dollars in extra inventory holding costs, hundreds of millions of dollars lost due to weaker basis values from higher freight costs, unquantified amounts on contract disputes, and the list continues. Those losses have to be absorbed somewhere in the handling chain. Car orders continue to lag, especially on the BNSF, but there are signs of improvement. Turn times on shuttles rose to 2.5 in May vs .2 in March/April, and values in the secondary car market for summer 2014 have dropped to almost zero. Moving inventories will still be a big task this summer, but the numbers seem manageable.

Agriculture has always been subject to the whims and mercies of Mother Nature. The losses of the Dust Bowl years were devastating and the Southern Plains region shows signs that more rough times lie ahead. The state of Kansas is 100% in moderate to exceptional drought, and all but a small portion of Oklahoma is the same. Nebraska has pockets of drought in the south and west, but the Northern Plains have had mostly adequate to surplus moisture. The prospects for big crops are there from Montana to Kansas — if conditions turn out good for row crops to help offset losses in wheat. But it’s always wise to recall The Worst Hard Time to recognize that weather, whether cyclical or climate-driven, can derail the best laid plans.